Celilo Falls, Before the Silence

There are places that shape a people long before they are named on a map.

Celilo Falls was one of them.

For more than ten millennia, the river narrowed and thundered along the edge of what is now the Columbia River, creating a place of movement, sound, and life. Salmon leapt. Voices carried. Trade flowed as steadily as the water itself. This was not simply a site of sustenance. It was a center of continuity—economic, spiritual, and cultural—where Indigenous nations gathered season after season, generation after generation.

In 1957, the river rose. With the completion of the The Dalles Dam, the falls were submerged. What had endured for thousands of years disappeared in a matter of hours. The sound was replaced by stillness. A living system was reduced to memory.

What remains now is absence—and record.

The Last Season

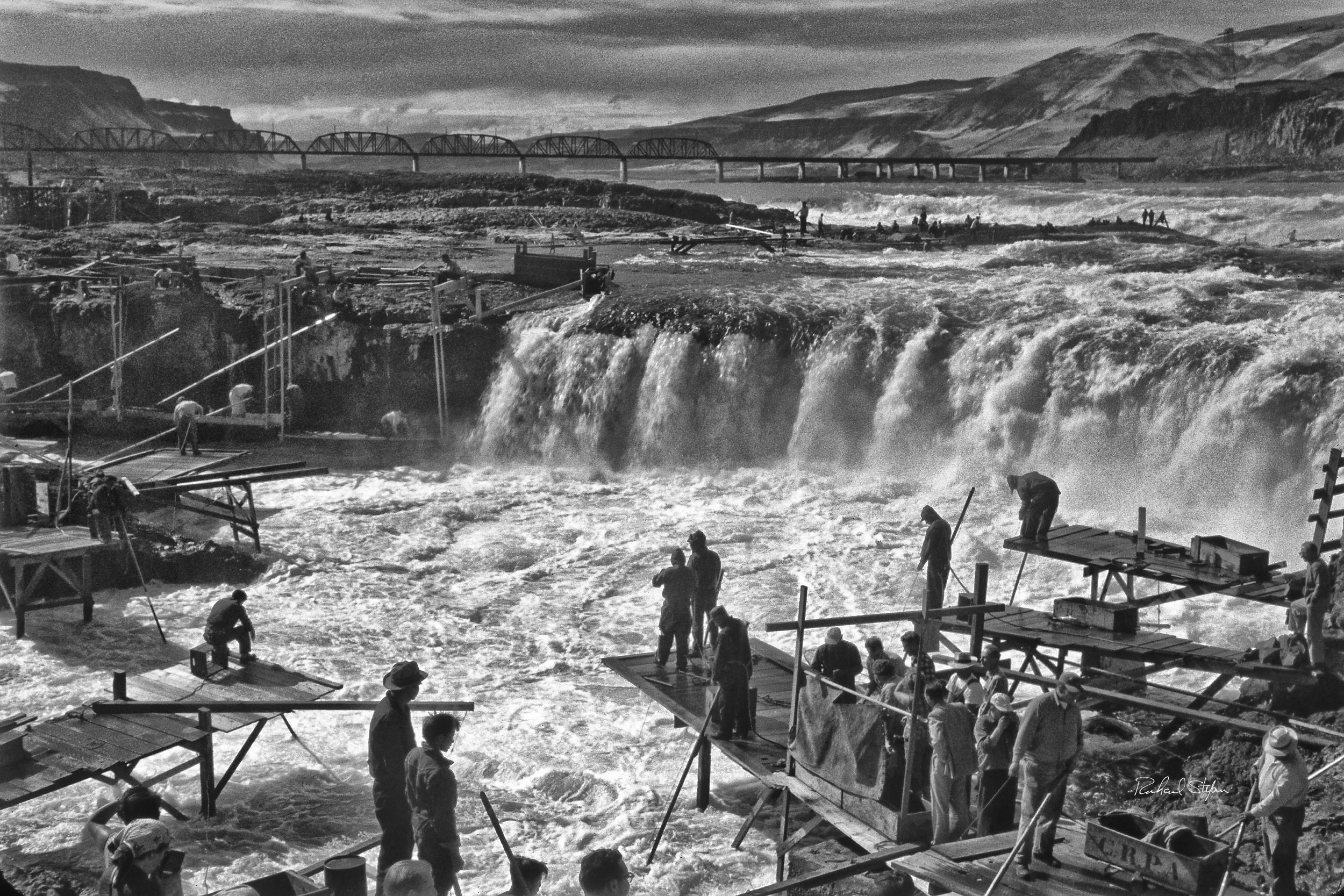

In the fall of 1956, one year before the waters erased the falls from view, photographer Richard Stefani stood at the river’s edge with a quiet sense of purpose. His black-and-white photographs from that season are not dramatic in the modern sense. They do not ask for attention. They hold it.

Fishermen balanced against spray and stone. Nets cut through air shaped by centuries of repetition. The river appears powerful, indifferent, and ancient—exactly as it was. There is no sense of spectacle. Only presence.

These images were made at the threshold of loss, though they do not announce it. That restraint is their strength. They allow the viewer to arrive on their own, to understand slowly what is about to vanish.

Net salmon fishing, 1956, © Richard Stefani

What Was Taken

For Indigenous communities, the loss was never abstract. The falls were a spiritual anchor, a place where ceremony and daily life were inseparable. Knowledge lived here—how to read the water, how to honor the fish, how to belong to a system larger than oneself.

When the falls were submerged, something essential was severed: a direct, physical relationship between land, river, and people. That rupture still echoes today, in conversations about stewardship, sovereignty, and the cost of progress measured without consent.

Photographs from this period do not replace what was lost. They cannot. But they do something equally important. They refuse erasure.

“Dignity”, 1956, © Richard Stefani

Why These Photographs Endure

Stefani’s work from 1956 stands apart because it was made without urgency and without agenda. It was shaped by observation, patience, and respect—qualities that define work meant to last.

To collect one of these photographs is not to acquire nostalgia. It is to accept responsibility. Each print carries cultural weight, historical truth, and the quiet authority of witnessing. They are documents, yes—but also objects of lasting beauty, composed with discipline and restraint.

These images belong in spaces where time matters. Where art is lived with. Where legacy is understood not as inheritance, but as care.

Living With History

At House of Stefani, we believe photographs can function as vessels—holding memory, meaning, and continuity long after the moment itself has passed. The 1956 Celilo Falls photographs are such vessels.

They ask nothing of the viewer except attention. In return, they offer a rare encounter with a place that shaped lives for thousands of years, and with an artist who understood when to step back and let the story remain intact.

Some landscapes are gone.

Some histories survive because someone chose to look carefully.

These photographs exist for that reason.

Photographs of Celilo Falls by Master Photographer Richard Stefani are available exclusively at Stefani Art Gallery.